Aurélien Rigotti is a PhD student working on sea ice rheology as part of WP2. He is supervised by Véronique Dansereau and Jérôme Weiss at the National Center for Scientific Research in Grenoble, France.

" I hope my work will play its part and continue to be discussed, criticized, and explored. Véronique, Jérôme, and I are contributing to a promising path for the rheology community."

An interview with Aurélien Rigotti.

By: Solène Guyard.

Tuesday, February 11, 2025.

What first drew you to the field of research?

I’ve always been concerned about climate change, and that concern led me towards research. Initially, I didn’t know where I was headed during my studies. I wanted to work in geology, something that wouldn’t contribute to climate issues. After starting in geotechnical engineering, I realized it wasn’t the right fit. So, I shifted to a Master’s in Geomechanics. At that time, I wasn’t sure where my career was going, but I applied for two internships. One was on couscous behavior in high humidity (which seemed too far from my interests), and the other was on sea ice as a granular medium. I’m lucky to have been hired for the second one—it completely shifted my focus, and it’s why I decided to pursue a PhD.

What subject did you study during your thesis and what did your research aim at understanding in the context of SASIP?

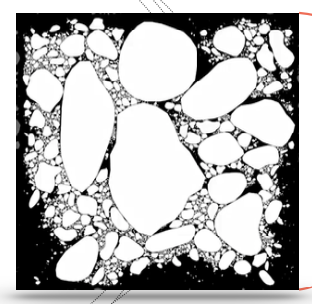

My PhD focuses on improving the MEB rheology, developed by Veronique, by accounting for the complex behavior of granular sea ice in the Arctic. Observations of the ice pack during the warmer season show that the material is discontinuous, made up of assemblies of sea ice plates, called floes, rather than being continuous. The models currently fail to accurately describe the behavior of such a sea ice cover.

Can you explain the choice of floe shapes and size distributions in your model? What makes them “realistic” compared to field conditions? ?

These granular ice pack is studied as a 2D rigid dry frictional granular assembly. To make this more understandable, the size of the plates, with respect to their thickness, allows us to neglect the height, and the water between the plates is assumed to be very small compared to the friction and collisions between the floes. The idea Veronique Dansereau and Jérôme Weiss had was to describe the mechanisms acting in an ‘idealized’ assembly of sea ice plates, where disks are studied instead of the complex floe shapes observed in the Arctic. The goal was to capture and understand the key phenomena driving the mechanical behavior. This is also why I focused on ‘rigid,’ unbreakable grains.

How did you identify the key variables or parameters to describe the mechanical state of the ice?

To identify the parameters characterizing the behavior of granular assemblies, we started with the MEB model. The rheology of the granular medium was expected to exhibit an initial instantaneous response, indicating elastic behavior, followed by a time-dependent behavior associated with viscosity. Lastly, a plastic element might also emerge in such a material. We then developed experiments to monitor these properties: small-amplitude oscillatory tests to quantify the elastic properties and relaxation tests, where the loading is removed and the volume of the system is kept constant, to assess the viscous-plastic response.

On the one hand, the small-strain oscillatory test shows a decrease in elastic properties with an increase in shear strain, highlighting the appearance of damage in the granular assembly. On the other hand, the relaxation test allows the measurement of time-dependent stress decay, indicating viscosity, and the observation of a residual stress plateau, consistent with plastic behavior.

These three parameters can then be compared to state variables monitored in a continuous model, such as packing fraction, concentration, and damage.

How does the granular concentration at small scales influence the mechanical properties observed at larger scales in your model?

Inter-scale dependence is a fascinating aspect of granular materials! Just like in continuum materials, such as rocks, concrete, or perennial sea ice, the formation of micro-cracks at the microscale leads to the development of faults and fractures at the macroscale, with dramatic impacts on the macroscopic mechanical response. In granular assemblies, chains of grains define the rigidity of the system, as well as its capacity to handle stress and strain. When a single grain in these chains moves, stress is instantaneously redistributed to surrounding particles and can lead to avalanches of grains until a new stable configuration is reached. Thus, grain concentration, or the packing fraction, and particularly the initial packing fraction, play a crucial role. A higher packing fraction means more grains to sustain loading and rigidify the system. However, applied pressure also plays an important role in granular materials, as it can radically change the observed behavior of the system.

Have you encountered any unforeseen results during your study?

The real surprise for us was how granular matter behaved during the relaxation test. In solids, fluids, or granular materials, when a load is applied to the system and later removed, a certain amount of time is needed to fully or partially dissipate the internal stress stored, in order to reach a stable state of equilibrium.

First, we observed relaxation that was slightly faster than typical fluid relaxation behavior. Secondly, the residual stress value at the end of the relaxation test decreased with the growth of damage. Finally, the characteristic timescale of this stress dissipation exhibited a non-trivial evolution, likely acting across different length scales of the granular assembly.

These are key results that would be fascinating to further explore

What real-world applications do you see for your findings, and how might they contribute to addressing global challenges like climate change?

Granular sea ice in the Arctic is currently poorly represented by continuum approaches, and discrete modeling is too computationally expensive to be integrated into coupled ocean-atmosphere-ice pack models. I hope the findings presented in my thesis will help improve continuum modeling by enhancing the material properties characterizing lower sea ice concentration zones with granular behavior. I’ll be optimistic in saying that we will see the outcomes of my work in climate prediction next year!

It’s also worth noting that, while the results obtained in my PhD are intended for direct application in SASIP WP2, they have a broader application to a wide range of frictional granular assemblies. Our understanding of such materials has greatly improved in the past fifty years, but many questions remain open. I hope my work will play its part and continue to be discussed, criticized, and explored. Véronique, Jérôme, and I are contributing to a promising path for the rheology community.

What advice would you give to young scientists or students interested in your field?

Tricky question! The only thing I would allow myself to say is: try. If someone thinks they might enjoy studying this field, it’s always worth exploring. Research is about curiosity, so it’s best to follow ours!